Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

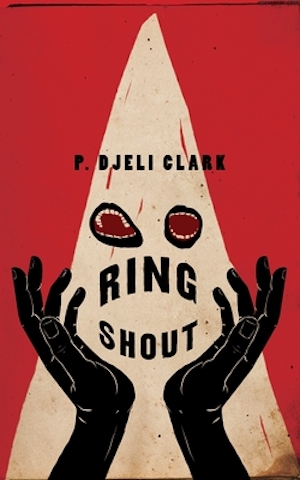

This week, we continue P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout, first published in 2020, with Chapters 3-4. Spoilers ahead!

“They are the lie.”

Frenchy’s Inn isn’t the only colored spot in Macon, but on this Fourth of July evening, it’s obviously the place to be. Maryse, Sadie and Chef arrive for a well-earned night off. Lester Henry joins their table, evidently hoping Sadie will break her rule of never spending a second night with the same man. Chef embraces Bessie, a local woman. Maryse has eyes only for “the finest thing in the room,” handsome St. Lucian Creole Michael George, aka Frenchy. Women swarm him, but Maryse is content to wait–Michael has assured her they’ll get together later.

Lester holds forth on Marcus Garvey’s idea that “the Negro has to go back to Africa and claim what’s ours.” Chef intends to stay in the country she fought for. Sadie takes interest when Lester talks about the “old Negro empires” and how once the “whole world was colored.” She supposes white folk are so mean because deep down they know they “come out of the same jungle” as Negroes.

Chef and Bessie, Sadie and Lester, retire upstairs. As Maryse and Michael George dance, Nana Jean’s ominous premonitions slip from her mind, and they soon repair to a room of their own.

After lovemaking, Maryse dreams she’s in her old home, a cabin outside Memphis that her great-grandfather built after escaping urban lynch-mobs. It looks just like when she left seven years before, a whirlwind-wreck of broken pots and toppled furniture. She lifts a hidden floor-hatch to reveal a terrified girl with her own eyes, clutching the silver-hilted sword she ought to have used instead of hiding. Maryse castigates her for interrupting her fights and now haunting her dreams. The girl refuses to emerge, in case “they” come back. “They watching,” she warns. “They like the places where we hurt. They use it against us.”

Before Maryse can learn who they are, her dream dissolves into blackness. Faint light leads her to a red-haired man wearing an apron. Singing off-key, he swings a cleaver into meat that squeals at the assault. Butcher Clyde is his name. We’ve been watching you a long time, he informs Maryse, and now she’s obligingly left space for them to slip in. As he resumes singing, jagged-toothed mouths open all over his body and join in an ear-raking chorus. Clyde rips off his apron to reveal a huge mouth in his belly. Maryse’s punch turns him into a pitch-black liquescent horror that drags her toward its maw….

She starts awake. Michael George sleeps on beside her; Maryse comforts herself remembering his stories of exotic travels and his suggestion that they get a boat and sail “the whole world round.” Uncalled, her sword appears. Compelled to grab its hilt, she’s transported to a green field under a sunless blue sky. Three women in Sunday finery, with the “knowing looks of aunties,” sit under an oak. One time Maryse pierced their illusion and saw tall creatures in red gowns, fox-like faces behind brown-skin masks. Nana Jean has warned that such “haints” are tricksy, but they’re the ones who gave Maryse her sword. They described its creation by an African slave trader who was himself sold into slavery. He forged the sword and called on the dead enslaved to bind to it himself and all enslaving kings and chiefs, making it a weapon of vengeance and repentance.

The aunties warn her that the “enemy is gathering.” The Ku Kluxes aren’t its only minions, nor the most dangerous–hearing about “Butcher Clyde,” the aunties are alarmed. Maryse must stay clear of him!

Back home, Maryse tells Nana Jean about Clyde. Nana Jean figures he’s the “buckrah man” of her premonitions. What’s more, he’s actually come to Macon to open “Butcher Clyde’s Choice Cuts & Grillery: Wholesome Food for the Moral White Family.” Against orders, Maryse straps on her sword and crashes Clyde’s grand opening. Klan members guard the storefront, two of them Ku Kluxes. White patrons have lined up for free samples of meat. Clyde calms their outrage with a speech about how “the lesser of God’s creatures at times need to be guided righteously to recall their proper place.”

He sits with Maryse, undaunted by her sword and the backup she’s stationed outside. There’s no need for theatrics. She’s come for answers her “aunties” won’t give. Is he a Ku Klux? No, Ku Kluxes are to him as a dog to Maryse, yet he’s more “management” than master. Why is he here? To fulfill the grand plan of “bringing the glory of our kind to your world” so humans may be “properly joined to our harmonious union.” They don’t favor whites over other races, but whites are “so easy to devour from the inside,” made vulnerable by their hate. As far as Clyde’s concerned, all humans are “just meat.”

He allows Maryse to see his true form, a monstrous collective moving under his false skin “like maggots in a corpse.” “Grand Cyclops is coming,” all his mouths croon, and when She does, Maryse’s world is over. But don’t worry, there’s a special place for Maryse in their grand plan.

At Clyde’s signal, a Ku Klux brings a plate of squealing meat to Maryse. White patrons avidly devour their portions. She stabs hers and heads out, Clyde calling after her that “we” will soon return the favor of her visit.

Nana Jean’s people gather at the farm, armed and vigilant. Apart from Clyde’s threat, there’s been Ku Klux activity state-wide, and Klans gather at Stone Mountain. Molly speculates the mountain may be a focal point where worlds meet. Could the “Grand Cyclops” appear there?

As Maryse and her fellows weigh holing-up over marching on Stone Mountain, a sentry ushers in a boy with a message: Klans are attacking Frenchy’s Inn!

This Week’s Metrics

What’s Cyclopean: The Grand Cyclops, presumably. But let’s avoid finding out.

The Degenerate Dutch: Lester gets Sadie’s attention by quoting Marcus Garvey on the African origins of civilization. Sadie’s interpretation is that white people are n—s (with a little n). She also rather likes the idea of Nubian queens.

Anne’s Commentary

Did any of us suppose that Nana Jean’s premonitions of bad psychic weather would prove overly pessimistic? After the horrific action of Chapter One and the tense exposition of Chapter Two, Clark’s monster-hunting bootleggers get a rare night out. As far as Maryse can tell, the indomitable Sadie parties hard and whole-heartedly; what darkness may underlie her vigor we’ve yet to learn. On the other hand, Chef doesn’t make it through a night even in Bessie’s arms without her wartime trauma resurfacing. Post reunion with Michael George, Maryse gets little rest. First she dreams, and then she’s invaded by the enemy, and then her cosmic mentors summon her to a debriefing. Damn, girl, you need an actual vacation.

Hell, girl, we know you’re not going to get one.

It’s a blessing mixed with a curse how the human mind works with metaphor. We can temper painful memories and emotions by projecting them into a surrogate construct. In Chapter One we met the Girl in a Dark Place whose phantom always accompanies the appearance of Maryse’s sword, and whose fear threatens to swamp the monster hunter in “a terrible baptism.” Maryse has come to expect the Girl as a preliminary to fighting. At such times she can dismiss the Girl and with her the incapacitating terror. But now the Girl’s invading Maryse’s dreams as well. Without the pressure of impending combat, Maryse has time to notice that the Girl has Maryse’s own eyes–looking at her is like looking into “a mirror of yesterdays.” The Girl is Maryse at a moment of terrible crisis, but she’s not who Maryse actually was at that moment. Critically, she is much younger, a child in a nightshirt, the image of allowable vulnerability. Who could expect a child to pick up that sword by her side and abandon safety for battle? It’s all right for the Girl to cower. Necessary, in fact, which makes her the perfect containment receptacle for Maryse’s terror, as she felt it during the yet-unspecified event in the cabin, and as she continues to feel it whenever confronted with the enemy.

The Girl doesn’t need to feel guilty for inaction. Too bad that in the self-clarity of Maryse’s dream, she must acknowledge that the Girl is no child. The Girl tells her so, after all, and the Girl must know. She’s Maryse at Maryse’s core, first responder to dangers that evade Maryse’s conscious mind, such as the fact that the enemy has breached their most intimate stronghold, the places where they hurt.

Butcher Clyde takes over Maryse’s dream but is no dream. He is a psychic invader, appearing in a human guise of his own choosing, not her subconscious construction. It’s the same guise he’ll present to Macon at large, as proprietor of a shop that supplies Choice Cuts to Moral White Families. What sets Maryse apart from Macon at large is her ability to see through enemy illusions to the bestial reality of the Ku Kluxes and the truly eldritch plasticity of Clyde, a middle management monster. To make sense of Clyde, Maryse falls back on the imagery of her brother’s favorite folk tales: Clyde’s the Tar Baby who snares Bruh Rabbit with his viscous black hide. Later, at his shop, Clyde obligingly tells Maryse what he really is, or rather who they really are: A glorious collective who abominate the “meaningless existence” of individualistic creatures like humanity. Kind of a Shoggothian version of the Borg?

The Grand Cyclopean Collective isn’t a racist organization, at least. Since all humans are just meat, they mean to properly assimilate everyone into their “harmonious union.” But I suspect that by “properly” Clyde means humans will join the union as a subordinate harmonic line. Notice how readily Clyde falls into racist human lingo when he speaks about putting the “lesser of God’s creatures” (as in Maryse) in “their proper place.”

He sure knows how to play to his audience, as do Maryse’s cosmic mentors. The Collective is their enemy, but they use the same strategy to deal with humans, mining cultural images and expectations for the illusions they should create for optimal effect. Maryse sees her mentors as “aunties,” Black women of greater wisdom than herself, loving or critical or eccentric but unfailingly supportive. They greet her under a Southern red oak, in their Sunday best, sweet tea at the ready. Maryse knows they’re not human. She even imagines they’ve constructed their guises from memories of her mother, but she still puts aside Nana Jean’s caution that “haints” are “tricksy” and is fond of them.

And that’s after she’s glimpsed what may be their true forms, “womanlike” but “unsightly tall,” wearing “bloodred” gowns and masks that may have been stitched from “real brown skin.” Most tellingly, the faces beneath these masks remind her of foxes. As she compared “real” Clyde to the Tar Baby, she draws on her same cherished vein of folklore to compare the “real” aunties to Bruh Fox.

If Maryse casts herself as Bruh Rabbit, that’s not necessarily an auspicious comparison.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Bad weddah, sure enough. We’ve already seen that our heroes can take on a few ku kluxes and come home singing with a prize of hooch. But what about management? What about hundreds of hate-driven humans, possessed by wickedness that they ate up willingly? What about whatever all those hateful “moral white” folks, drawn into “harmonious union,” are ready to summon?

That sounds harder.

My kids are currently making their way through A Wrinkle in Time for their evening reading, so I’m predisposed to be suspicious of entities offering to take over your burden of independent thought, not to mention offering food that isn’t as tasty as it seems. Butcher Clyde seems like a particularly unappealing version, but they certainly know their audience. Talking to someone who isn’t their audience, though, they can’t resist gloating—even as they claim to have something Maryse wants. She would have to want it pretty badly…

And we do see earlier what she does want badly, and it is pretty appealing. Frenchy’s is pure joy, the kind of escapism that gets you through hard times and hard duties. It’s a place where intellectuals can draw you in talking about lost histories, where gender is what you want it to be and all kinds of lovers are welcome on the dance floor, and where the owner has an accent to die for. And where even if he doesn’t know what pulls his lady away for weeks at a time, that owner is very willing to offer distraction and consolation. His complete disconnect from the world of supernatural battles seems like both a barrier and one of the things Maryse finds so attractive. Getting away from those battles—even if it’s not something she’s actually willing to do—“sounds like freedom.”

Joy is a necessary antidote to hard times, but also a vulnerability. One that Butcher Clyde and his ilk are pleased to take advantage of. There’s no such thing as a safe place when the enemy already knows you.

And the enemy does seem to know Maryse. Something in her past has given them a way in. It’s not clear yet whether that opening was the trauma of whatever happened to the girl under the floorboards, or Maryse’s current refusal to talk about it. There’s certainly a brittle danger in that refusal, and in its breadth. She not only won’t talk about it to her colleagues, she avoids it with Frenchy (with whom she has precious few actual topics of conversation available), with her own past self, and with the mysterious elder mentors who might actually be able to help. The aunties gave her that lovely sword, but Nana Jean’s not the only person with ambivalent feelings about them. Though I don’t think it’s just “haints”—Maryse’s general attitude towards wise advice seems to be that it’s a great thing to consider while doing just the opposite.

It’s hard to blame her, though. After all, what Maryse wants is fair play—the enemy knows her, so shouldn’t she know the enemy? Of course, he problem with a lie pretending to be truth is that even if you know it’s a lie, you can’t always tell exactly what it’s lying about. I think, though, that a big part of Butcher Clyde’s lie goes back to the original racist fears that fed the original cosmic horrors. Lovecraft was terrified that in the grand scheme of things, anglo civilization was an illusion. That humans were equal, and that the only way to be equal was in unimportance and meaninglessness. That’s the type of equality that Clyde offers: “Far as we concerned, you all just meat.” And the big lie is that that’s what equality looks like, and the only thing it can look like.

Good thing no one’s spreading that lie around in real life, yeah?

Next week, we go back to a 1923 Southern gothic whose setting might not be too far off from Clark’s; join us for Ellen Glasgow’s “Jordan’s End.” You can find it in Morton and Klinger’s Weird Women.

Ruthanna Emrys’ A Half-Built Garden comes out in July 2022. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

…having now read the Glasgow, the setting is not really even a little bit like Clark’s.

I can basically attest to Sadie’s idea that racism comes from our (white folks’) jealousy. There’s a great photographer, Deana Lawson, who said when she was growing up there was a confusion in her between the obvious beauty, dignity, REGAL-ness of her Black loved ones and the way they were treated. And Jennifer Egan has a gorgeous line, “once you have loved a person with dark skin, light skin seems drained of something vital.”

Chef is gay, right? Please?

Thanks to Molly Encrypted for noticing that the first installment of this wasn’t in the list! I’ve been haunting for weeks, wondering if AP and RE were on holiday!

This story got big quick! There don’t seem like enough pages to resolve a battle of such cosmic proportions!

A minor observation, but I like how these cosmic entities are mimicking human culture as a way to communicate with their…prey? pawns? It’s an obvious in, but I also feel like it makes clear that the stories humans tell in this world are worth something, and are their own. Even if it becomes dressing for the true horrorshow that is Butcher Clyde, feeding off the hate that already exists in our hearts, and using our fears as a gateway. I also love how the aunties are from the same narrative thread as A Wrinkle in Time, but also can’t hide that they have a lineage far more distressing.

I had to finish the book in 2 sittings both to find out what happens and to get it back to the library (it’s very popular) so I’ll hush my mouth till the conclusion!